The world is witnessing an unprecedented scramble for rare earth minerals—a race reshaping global alliances, powering technological breakthroughs, and redefining 21st-century power. From smartphones to fighter jets, these 17 enigmatic elements have become the vitamins of modern industry.

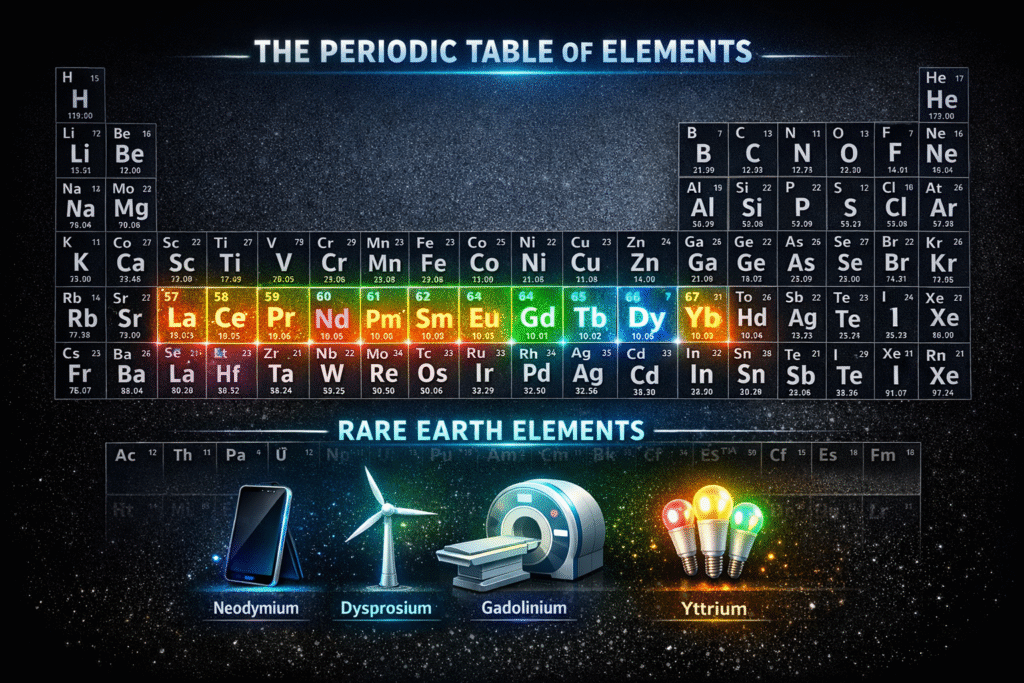

The 17 Elements Powering Our Future

Despite their name, rare earth elements aren’t actually rare—finding economically viable concentrations is the challenge. These elements possess unique magnetic, luminescent, and conductive properties that make them irreplaceable.

Light Rare Earths:

- Lanthanum (La) – Camera lenses, batteries

- Cerium (Ce) – Catalytic converters, glass polishing

- Praseodymium (Pr) – Permanent magnets, jet engines

- Neodymium (Nd) – World’s strongest magnets

- Promethium (Pm) – Radioactive, trace amounts only

- Samarium (Sm) – Defense magnets

- Europium (Eu) – TV screens, currency anti-counterfeiting

- Gadolinium (Gd) – MRI contrast agents

- Scandium (Sc) – Aerospace aluminum alloys

Heavy Rare Earths (scarcer, more valuable):

- Terbium (Tb) – High-efficiency motors

- Dysprosium (Dy) – EV motors, wind turbines

- Holmium (Ho) – Lasers, nuclear control

- Erbium (Er) – Fiber-optic telecommunications

- Thulium (Tm) – Medical lasers (rarest)

- Ytterbium (Yb) – Stainless steel, lasers

- Lutetium (Lu) – PET scan detectors

- Yttrium (Y) – LEDs, superconductors, cancer drugs

Why They Matter:

- Each electric vehicle needs 1-2 kg of rare earth magnets

- A single wind turbine uses up to 600 kg of rare earths

- Critical for defense systems, missiles, and advanced electronics

- Essential for smartphones, laptops, and medical imaging

- Demand projected to reach 3-7 times current levels by 2040

Learn more about electric vehicle technology and sustainability

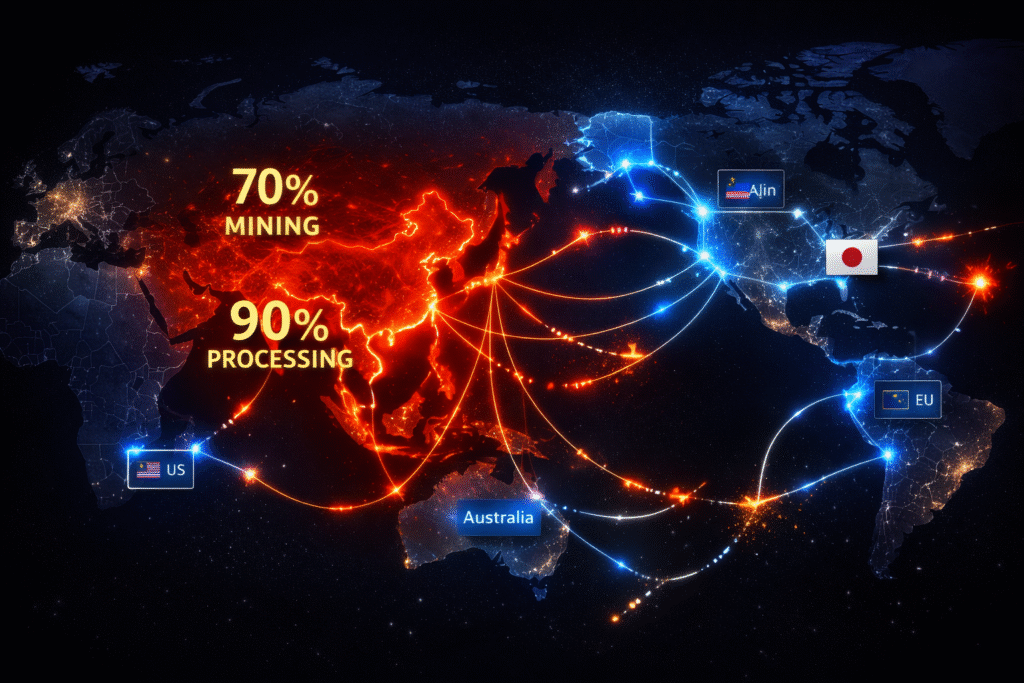

China’s Chokehold and Weaponization

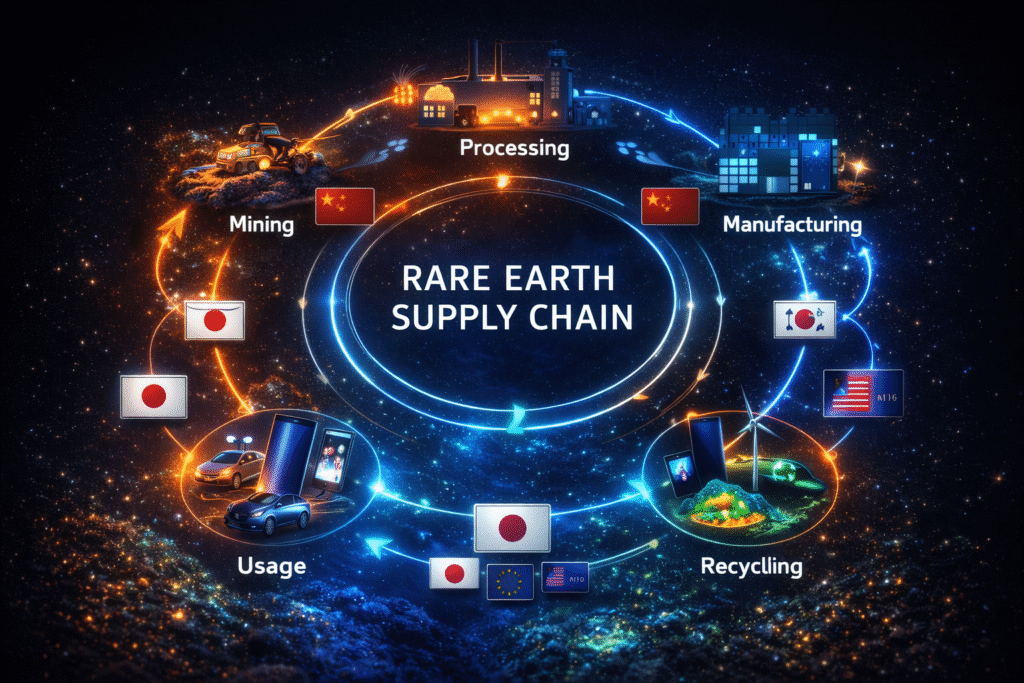

China controls 70% of global rare earth mining and 90% of processing—and it’s weaponizing this dominance:

Historical precedent: In 2010, China cut rare earth exports to Japan during a territorial dispute.

Latest escalation (January 6, 2026): China banned exports of dual-use items to Japan after Prime Minister Takaichi stated a Chinese invasion of Taiwan would trigger Japanese military response. The ban covers roughly 1,100 items, including seven categories of medium and heavy rare earths (samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium). Japan, which relied on China for 63% of its rare earth imports in 2024, immediately protested.

Read about global supply chain security

China has also restricted exports of silver, tungsten, and antimony, naming just 44 authorized silver exporters for 2026-27.

| Quad Critical Minerals Initiative (July 2025) | The U.S., Japan, India, and Australia launched an ambitious partnership combining Australia’s mining resources, Japan’s processing expertise, India’s growing market, and U.S. manufacturing capabilities. Focus areas include electronic waste recycling and diversified supply chains. |

| U.S.- Australia Agreement (October 2025) | An $8.5 billion deal including $1 billion in immediate financing for priority projects and Pentagon investment in a 100-ton-per-year gallium refinery in Western Australia. |

| U.S.-Ukraine Minerals Deal (April 2025) | A joint reconstruction fund where Ukraine contributes 50% of revenues from new natural resource projects (titanium, lithium, rare earths). However, experts remain skeptical due to war damage and security risks. |

| India’s National Mission (January 2025) | ₹34,300 crore ($4+ billion) over seven years for 1,200 exploration projects and over 100 critical mineral blocks to be auctioned. India currently imports 53,000 metric tons of rare-earth magnets annually. |

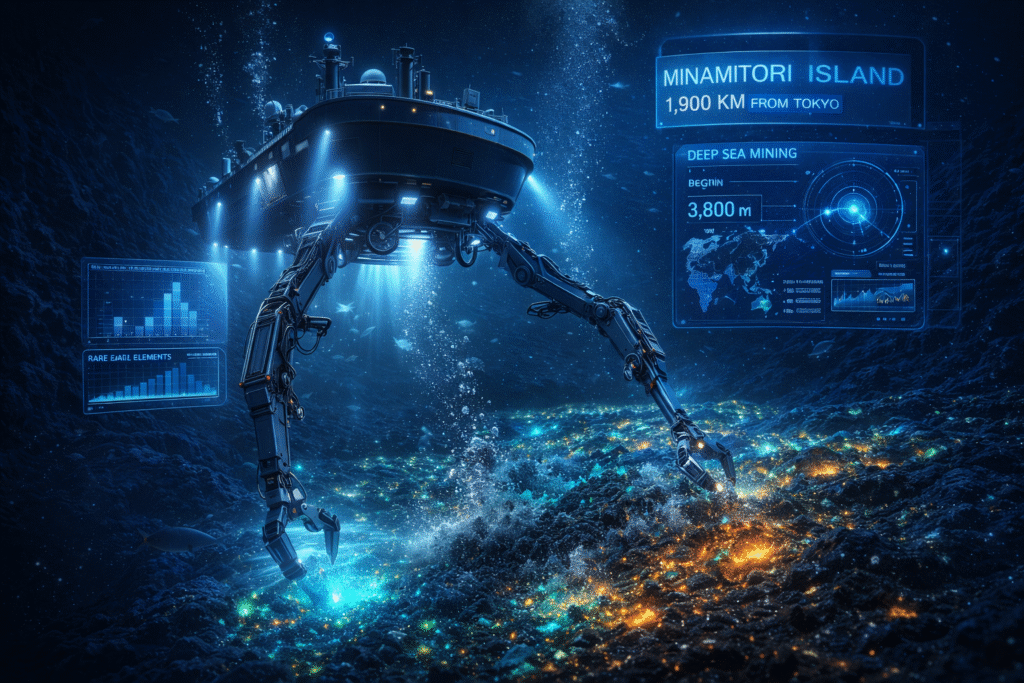

| Japan’s Deep-Sea Mining (January 2026) | Japan launched the world’s first deep-sea rare earth mining test mission near Minamitori Island, 1,900 km off Tokyo—a long-term strategy to achieve self-sufficiency after China’s repeated export restrictions. |

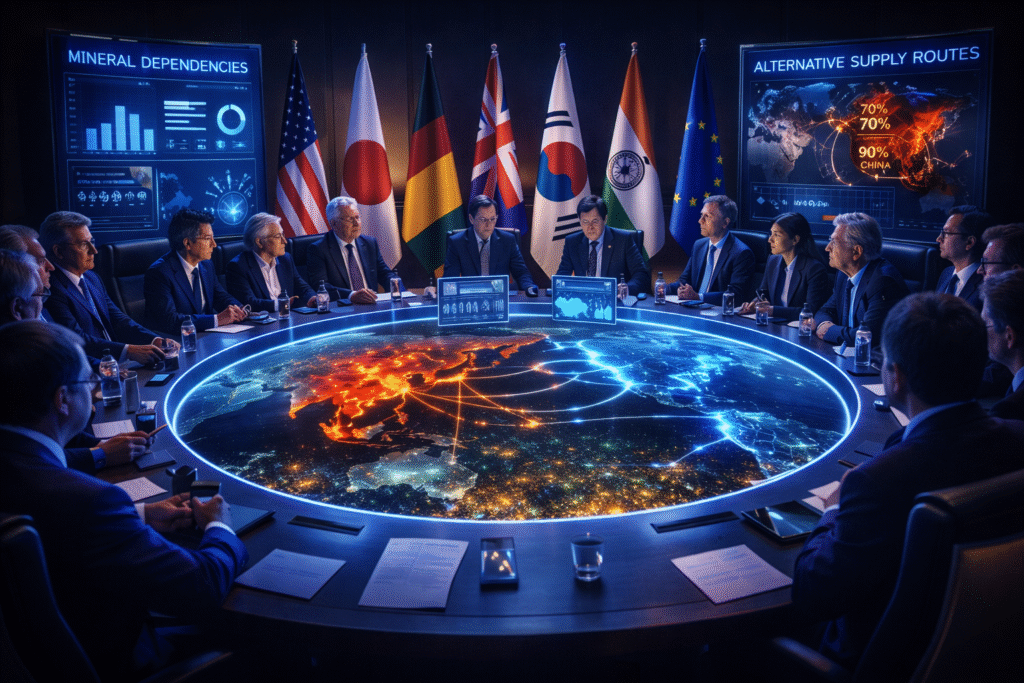

Latest G7 Emergency Meeting (January 12, 2026)

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent convened finance ministers from G7 plus Australia, India, South Korea, Mexico, and the EU—representing 60% of global critical mineral demand. Measures discussed include price floors, carbon tariffs on Chinese exports, and tighter investment screening.

Japanese Finance Minister Satsuki Katayama stated: “It is unacceptable for countries to secure monopolies through non-market means.”

Other Key Developments:

- Australia’s Strategic Reserve: A$1.2 billion prioritizing antimony, gallium, and rare earths

- French Aerospace Alarm: 90% dependence on Chinese rare earths with Beijing asking “intrusive” questions about end-uses

The Greenland Question: Trump’s Arctic Ambition

President Trump’s renewed push to acquire Greenland has thrust the Arctic territory into the global spotlight, highlighting what some see as untapped mineral wealth and others view as an economically irrational fantasy.

Greenland’s Mineral Potential:

- Estimated 36-42 million metric tons of rare earth oxides—potentially the world’s second-largest reserve after China

- Ranks eighth globally in proven rare earth reserves (1.5 million tons economically viable)

- Home to Kvanefjeld (third-largest known land deposit) and Tanbreez (potentially world’s largest at 28.2 million metric tons)

- Contains 25 of 34 minerals deemed “critical” by the European Commission

- Rich in uranium, copper, graphite, lithium, gallium, and germanium

The Trump Administration’s Strategy:

- June 2025: U.S. Export-Import Bank offered $120 million loan to Critical Metals for Tanbreez mine

- October 2025: Reuters reported U.S. considering buying stake in mining companies

- January 2026: Trump declared “one way or another, we’re going to have” Greenland

- Former National Security Adviser Mike Waltz: “This is about critical minerals. This is about natural resources.”

Market Response:

- Critical Metals stock: +241% over three months, +116% since start of 2026

- Energy Transition Minerals (Kvanefjeld owner): +30% on Trump’s latest statements

- Tech investors from Magnificent Seven companies now backing Critical Minerals projects

The Reality Check: Despite the hype, experts warn Greenland mining faces severe obstacles:

- Infrastructure crisis: Virtually no roads connecting settlements, limited ports, insufficient energy production. Mining would cost “billions upon billions” over decades.

- Ore quality issues: Greenland’s rare earth concentrations are 1.43% at Kvanefjeld versus 6.40% at Australia’s Mt Weld or 5.96% at California’s Mountain Pass. Lower grades mean more rock must be processed for less usable material.

- Climate challenges: 80% ice-covered, Arctic conditions make extraction 5-10 times more expensive than elsewhere. As one expert noted: “You might as well mine on the moon.”

- Processing bottleneck: Even if mined, materials would still need Chinese processing facilities—defeating the entire purpose of reducing dependence on Beijing.

- Timeline reality: No rare earth projects have entered commercial production. Best-case scenarios estimate decades before operations begin.

- Local opposition: Only 6% of Greenlanders favor joining the U.S.; 85% oppose it. “Everything American is a red flag,” warns Greenland Business Association.

The Geopolitical Complication: China’s Shenghe Resources owns 12.5% of the Kvanefjeld mine and signed a 2018 MOU to lead processing and marketing. Greenland’s mining minister warned that without Western investment, the territory may turn to Chinese partnerships.

Malte Humpert of The Arctic Institute called the idea of Greenland as America’s rare-earth factory “science fiction” and “completely bonkers.” Mining economics expert Ian Lange agrees: “It certainly doesn’t make any sense as a rare-earth story.”

However, mining companies remain optimistic. Critical Metals CEO Tony Sage emphasized strong relationships with both Greenland and U.S. governments, while noting tech investors’ particular interest in heavy rare earths essential for defense, robotics, semiconductors, and aerospace.

Strategic vs. Economic Reality: While Greenland offers strategic positioning between the U.S. and Russia, proximity to Arctic shipping lanes, and alliance with the West, the economic case for rare earth mining remains dubious. As experts emphasize, rare earths aren’t rare—it’s purely an economic question of extraction costs versus versus returns.

Explore geopolitical impacts on technology

The Geopolitical Endgame

Jack Lifton, Co-Chairman of the Critical Minerals Institute, warns: “Critical minerals are now dictating political decisions between countries. Globalization is over. The world is reverting to form. It’s every nation for itself.”

Global manufacturing is splitting into two systems: efficiency-driven networks (centered on China) and security-driven networks (built by allied democracies). Companies are abandoning just-in-time models for stockpiling and long-term contracts.

However, China’s weaponization may backfire. Every threat strengthens other nations’ resolve to finish building alternative supply chains. In 2010, alternatives were embryonic. In 2026, they’re real, funded, and producing.

As climate economist Gernot Wagner noted: “Despite political attempts to stop or derail things, the clean-energy transition is happening—and it is accelerating—and it depends on critical minerals, whose prices are bound to jump.”

The nations and companies succeeding in this race won’t just profit—they’ll shape technology for generations. Power in critical minerals belongs not to those who threaten supply, but to those who can no longer be threatened.

Read more about global technology trends

For updates on critical minerals, follow: International Energy Agency | U.S. Geological Survey | CSIS Critical Minerals Program